I notice pictures that are crooked on the wall.” “I still have a very picky, precise mind, to a fault. “It was like working logic puzzles - big, complicated logic puzzles,” Wilkes says. A good programmer was concise and elegant and never wasted a word.

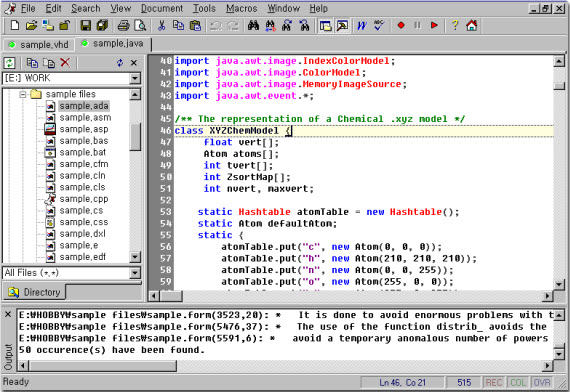

#Programming software for pc code#

The capacity of most computers at the time was quite limited the IBM 704 could handle only about 4,000 “words” of code in its memory. So she had to pore over her lines of code, trying to deduce her mistake, stepping through each line in her head and envisioning how the machine would execute it - turning her mind, as it were, into the computer. Often enough, Wilkes’s code didn’t produce the result she wanted. The computer executed the program and produced results, typed out on a printer. She would carry boxes of commands to an “operator,” who then fed a stack of such cards into a reader. There were no keyboards or screens Wilkes had to write a program on paper and give it to a typist, who translated each command into holes on a punch card. She first worked on the IBM 704, which required her to write in an abstruse “assembly language.” (A typical command might be something like “LXA A, K,” telling the computer to take the number in Location A of its memory and load it into to the “Index Register” K.) Even getting the program into the IBM 704 was a laborious affair. Wilkes quickly became a programming whiz.

Wilkes happened to have some intellectual preparation: As a philosophy major, she had studied symbolic logic, which can involve creating arguments and inferences by stringing together and/or statements in a way that resembles coding. (Stanford, for example, didn’t create a computer-science department until 1965.) So instead, institutions that needed programmers just used aptitude tests to evaluate applicants’ ability to think logically. The discipline did not yet really exist there were vanishingly few college courses in it, and no majors. But in those days, almost nobody had any experience writing code. It might seem strange now that they were happy to take on a random applicant with absolutely no experience in computer programming. “Do you have any jobs for computer programmers?” she asked. and marched into the school’s employment office. So on the day of her graduation, she had her parents drive her over to M.I.T. She knew that the Massachusetts Institute of Technology had a few of them. In college, she heard that computers were supposed to be the key to the future. More likely, she would be a law librarian, a legal secretary, someone processing trusts and estates.īut Wilkes remembered her junior high school teacher’s suggestion. If she lucked out and got hired, it wouldn’t be to argue cases in front of a judge. And if you get out, you won’t get a job,’ ” she recalls. Her mentors all told her the same thing: Don’t even bother applying to law school. The first digital computers had been built barely a decade earlier at universities and in government labs.īy the time she was graduating from Wellesley College in 1959, she knew her legal ambitions were out of reach. One day in junior high in 1950, though, her geography teacher surprised her with a comment: “Mary Allen, when you grow up, you should be a computer programmer!” Wilkes had no idea what a programmer was she wasn’t even sure what a computer was. As a teenager in Maryland in the 1950s, Mary Allen Wilkes had no plans to become a software pioneer - she dreamed of being a litigator.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)